The Spirit Domain of Everyday Resilience

Setting the Scene

In today’s article, we focus on the Spirit domain of the Everyday Resilience Framework. To date, we have discussed the Body domain, Community domain, and the Mind domain, highlighting the range of opportunities they offer to improve your personal resilience.

We’ve also emphasised how each of the domains interact with one another, noting that if you let one domain decline, it can drag down the others to weaken your overall resilience. You must remember that a holistic approach to developing resilience across all five domains is the key to maximising your resilience potential.

Todays Domain: The Spirit

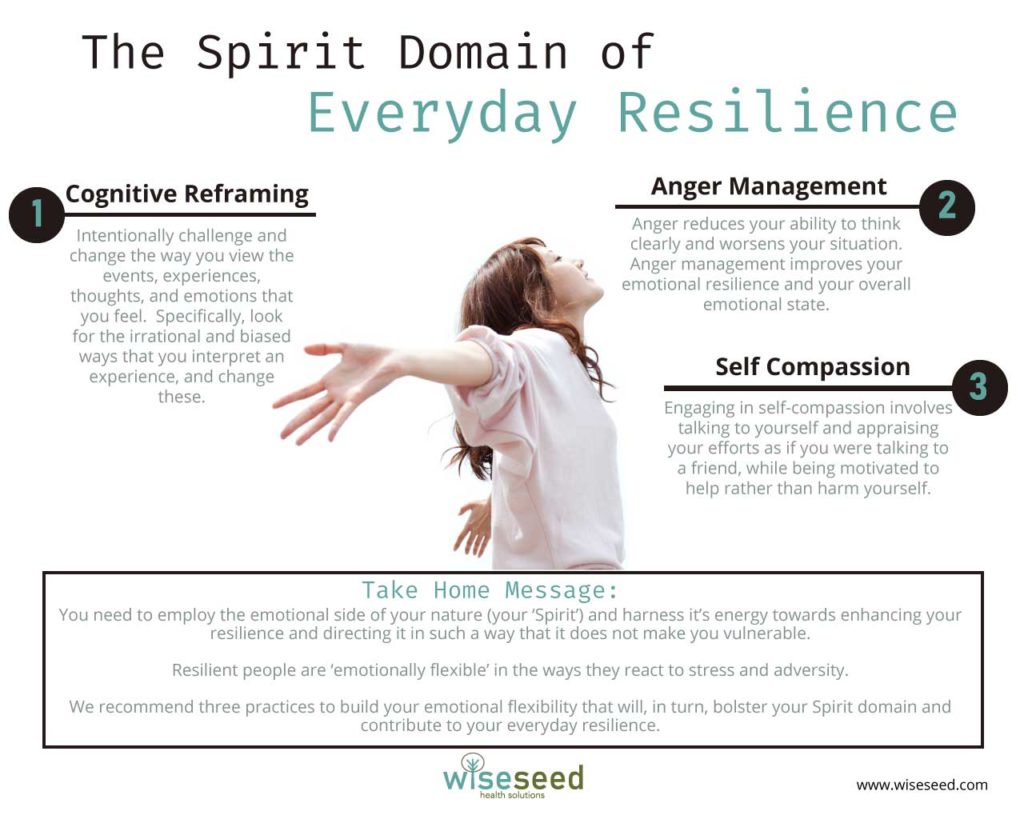

In the Mind domain article, we explained the need to optimise your cognitive performance to best contribute to your everyday resilience. Today, we consider how to employ the inherently emotional side of your nature (your ‘Spirit’) and harness its energy towards enhancing your resilience or directing it in such a way that it does not make you vulnerable.

It is well-established that your emotions play an incredibly powerful part in how you react to adversity and challenge (1). They colour how you perceive and interpret what is happening to you, trigger specific physical responses, and influence what decisions you make.

Importantly, this article is not about trying to ‘switch off’ your emotions or pretending that humans are not emotional beings. Its more about being aware of what triggers your emotions, the biases that influence how you interpret the things that happen, and having an understanding of how you can influence your emotional state. When you work to understand your inherent emotionality, you are better positioned to ‘domesticate’ your negative emotional states and have them work in your favour.

Rather than being unemotional, resilient people tend to be ‘emotionally flexible’ in the way they react to stress and adversity (2, 3). In the academic sense, emotional flexibility involves being able to change your emotions in a context-appropriate manner and to recover from the primary emotional response when the context changes, thereby creating the best possible match with the ever-changing environment (4).

In a practical sense, it’s about being flexible in re-calibrating your emotions to suit the current context. It’s the practice of experiencing joy at your child’s birthday party, and not be a simmering, impatient, mother or father still furious with a work call from earlier that morning. Or it’s about being able to perceive and positively respond to some incoming good news, and not remain flat and negatively re-interpret the message because the bus was late. The world around us is a rapidly changing and complex environment, and we need to be flexible in how we emotionally respond to the range of situations, information, and people that we encounter to be at our most resilient.

Three Practices that will Build your Spirit Domain

We recommend three practices to build your emotional flexibility that will, in turn, bolster your Spirit domain and contribute to your everyday resilience. These are:

– practising cognitive reframing

– anger management

– engaging in self-compassion

1. Practicing cognitive reframing

A prevailing outlook that affects all humans is our negativity bias. This means that humans generally default to the negative perception of an event and have a disproportionate bias towards looking for, and communicating, the downside of things (5, 6). We are also able to recall our negative experiences (such as failure) much more readily than our positive experiences (such as success) (7).

This inherent trait makes humans disproportionately look for the negative side in the world as a default perception, rather than take a more balanced evaluation of appraising the world and the things that happen to us. This means that you can spend our finite resilience resources on erroneously-perceived sources of stress and adversity that do not actually exist, or are very unlikely to happen.

One way to address this biased negativity is to engage in healthy cognitive reframing. The essential idea here is that you intentionally, but realistically, challenge and change the way you view the events, experiences, thoughts, and emotions you feel. You specifically look for the faulty, irrational, and biased ways that you interpret an experience and change these, because the way we think about things strongly affects our emotional state (8).

We’ll be writing future articles about cognitive reframing and how you can practice it for yourself. For now, simply note that it’s not an easy thing to do, as you are challenging some potent human biases and entrenched thinking habits. Still, it’s a powerful way of influencing how you perceive and emotionally experience the world around you while cultivating your personal resilience.

Anger management

One of the most diminishing effects on your resilience is being unable to manage the episodes of anger that we instinctively feel when navigating the challenges of the world. Anger, particularly when it manifests in an uncontrolled way, rapidly erodes the resilience we have intensively worked to build up over time.

Anger initiates physiological responses that reduce our ability to think clearly (9) and respond in clumsy ways that make you vulnerable to retaliation or worsens the situation. At the peak of anger, you are often reduced to the biology of your worst self, only to be followed by feelings of regret and shame (10), alongside permanently damaged social connections that you need as part of the Community domain. The effects of anger can also linger long after the event that triggered it (11), creating a sense of simmering rage, distracting thoughts of revenge, and recurring negative visualisations that eat away at your Body, Mind, and Community domains of resilience.

Engaging in anger management improves your emotional resilience and your overall emotional state (12). There are a variety of approaches available to engage with the practice of anger management, but we note the formidable ability of yoga to assist with anger management (refer to Angus’ article here), as does exercise (13) – we can’t have a Wise Seed article that doesn’t mention exercise!

3. Engaging in self-compassion

A key element of emotional flexibility is the use of self-compassion. In this article, we refer to self-compassion as a way of relating to yourself positively by being compassionate rather than unceasingly critical and demeaning of yourself (14). You often internally say, think, and repeatedly reinforce negative internal narratives about ourselves that we would never say to a friend or a family member. Critically, negative self-judgement erodes your emotional flexibility (15) and your overall emotional resilience.

Engaging in self-compassion involves talking to yourself and appraising your efforts as if you were in an internal dialogue with a friend, and being motivated to help rather than harm yourself (16, 17). It’s about:

– being kind, rather than hostile and brutal about your failures and mistakes

– recognising that failures are a shared human experience and a normal part of the broader human condition

– acknowledging when negative emotions have been triggered, but consciously intervening to prevent them from ‘taking over’ and dominating your thinking and outlook

Sadly, there are all sorts of people in the world – including individuals from the dark tetrad – that are all too ready to say negative things about you. You don’t need to add to that noise by unfairly beating up on yourself or inventing an understanding that failure and mistakes are things that only happen to you.

Looking Ahead

In our next article, we will consider the final domain of the Everyday Resilience Framework: Purpose. Creating a sense of personal purpose is hard, confronting, and sometimes painful. However, if you create a sense of authentic purpose and work towards achieving it over time, its contribution to your overall resilience cannot be underestimated.

Please click on the link below to download the free PDF of this article.

References and Further Reading

1. Jha, A.P., Morrison, A.B., Parker, S.C. et al. “Practice Is Protective: Mindfulness Training Promotes Cognitive Resilience in High-Stress Cohorts.” Mindfulness 8, 46–58 (2017).

2. Southwick, Steven M., and Dennis S. Charney. “Cognitive and Emotional Flexibility.” Chapter. In Resilience: The Science of Mastering Life’s Greatest Challenges, 165–83. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139013857.011

3. Meesters, Astrid, Linda MG Vancleef, and Madelon L. Peters. “Emotional flexibility and recovery from pain.” Motivation and Emotion 43, no. 3 (2019): 493-504.

4. Ibid

5. Bebbington, Keely, Colin MacLeod, T. Mark Ellison, and Nicolas Fay. “The sky is falling: evidence of a negativity bias in the social transmission of information.” Evolution and Human Behavior 38, no. 1 (2017): 92-101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2016.07.004

6. Cherry, Kendra. “What Is the Negativity Bias?” Very Well Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/negative-bias-4589618 Accessed 22 September 2020.

7. Baumeister, Roy F., and Brad Bushman. Social psychology and human nature, brief version. Nelson Education, 2010.

8. Robson Jr, James P., and Meredith Troutman-Jordan. “A Concept Analysis of Cognitive Reframing.” Journal of Theory Construction & Testing 18.2 (2014).

9. Lerner, J., and Katherine Shonk. “How anger poisons decision making.” Harvard Business Review 88, no. 9 (2010): 26.

10. Hansen, Sven. How to Master your Anger. The Resilience Institute. https://resiliencei.com/2017/07/master-your-anger/ Accessed 22 September 2020.

11. Cassiello‐Robbins, Clair, and David H. Barlow. “Anger: The unrecognized emotion in emotional disorders.” Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 23, no. 1 (2016): 66-85.

12. Turan, Nazan. “An investigation of the effects of an anger management psychoeducation programme on psychological resilience and affect of intensive care nurses.” Intensive and Critical Care Nursing (2020): 102915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102915

13. Shahbazzadeh, Somayeh, and Mohammad Reza Beliad. “The Mediatory Role of Exercise Self-Regulation in the Relationship between Personality Traits and Anger Management of Athletes.” International Education Studies 10, no. 5 (2017): 181-187.

14. Beshai, Shadi, Jennifer L. Prentice, and Vivian Huang. “Building blocks of emotional flexibility: Trait mindfulness and self-compassion are associated with positive and negative mood shifts.” Mindfulness 9.3 (2018): 939-948.

15. Ibid.

16. Ferrari, Madeleine, Caroline Hunt, Ashish Harrysunker, Maree J. Abbott, Alissa P. Beath, and Danielle A. Einstein. “Self-compassion interventions and psychosocial outcomes: A meta-analysis of RCTs.” Mindfulness 10, no. 8 (2019): 1455-1473.

17. Chen, Serena. “Give Yourself a Break: The Power of self-Compassion.” Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2018/09/give-yourself-a-break-the-power-of-self-compassion Accessed 22 September 2020.

Disclaimer

The material displayed on this website is provided without any guarantees, conditions or warranties as to its accuracy.

Information written and expressed on this website is for education purposes and interest only. It is not intended to replace advice from your medical or healthcare professional.

You are encouraged to make your own health care choices based on your own research and in conjunction with your qualified practitioner.

The information provided on this website is not intended to provide a diagnosis, treatment or cure for any diseases. You should seek medical attention before undertaking any diet, exercise, other health program or other procedure described on this website.

To the fullest extent permitted by law we hereby expressly exclude all warranties and other terms which might otherwise be implied by statute, common law or the law of equity and must not be liable for any damages whatsoever, including but without limitation to any direct, indirect, special, consequential, punitive or incidental damages, or damages for loss of use, profits, data or other intangibles, damage to goodwill or reputation, injury or death, or the cost of procurement of substitute goods and services, arising out of or related to the use, inability to use, performance or failures of this website or any linked sites and any materials or information posted on those sites, irrespective of whether such damages were foreseeable or arise in contract, tort, equity, restitution, by statute, at common law or otherwise.

Ten Minutes is All You Need

Research has shown that ten minutes of moderate-to-vigorous exercise performed each day is enough to significantly reduce your risk of early death.

Want to become anti-frail? Then consider a Fasting-Mimicking Diet.

Fasting-mimicking diets induce a fasting state while providing essential micro-nutrients, significantly reducing the risk of malnutrition.