The Five Pillars of Successful Aging

Take Home Message

1. Our longer lives have led to dramatic increases in rates of age-related disease and disability.

2. Lifestyle interventions can increase the chance of living a long and successful life.

3. We have classified these interventions into five broad lifestyle strategies: (1) Exercise; (2) Diet; (3) Sleep; (4) Achievement of Life Goals and (5) A Strong Social Network.

4. These five strategies are effective and available to everyone.

Introduction

Compared to an average life expectancy of 45 years in 1900, life expectancy is now around 82 years 1,2. As the population ages, age-related diseases are steadily increasing. The average person can now expect ten years of disability and chronic disease at the end of their life.

The good news is that researchers are discovering new ways to minimize or avoid the effects of age-related disease 3. The five pillars of successful aging are designed to help you avoid age-related disability, maintain a high cognitive capacity, and actively engage with life.

Successful Aging

Evidence is steadily growing in support of the hypothesis of successful aging. For example, some people living to over a hundred years old display extremely good health until just before death 4. However, individuals who live beyond 100 years are rare indeed. Thus, it’s impossible to identify whether genetic or environmental factors are responsible for their successful aging.

Of much greater relevance are studies of individuals who age successfully by practicing a healthy lifestyle 5-8. Very recent data show that a healthy lifestyle significantly reduces all-cause mortality and the incidence of cancer 9. This shows that healthy lifestyle interventions offer a path to successful aging that is available to everyone, including you.

What are the five pillars of successful aging?

Data from centenarian and healthy lifestyle studies cited above show that successful aging is indeed possible. Further, direct comparisons between healthy versus Western lifestyles suggest that lifestyle interventions are an effective strategy for successful aging 5-9.

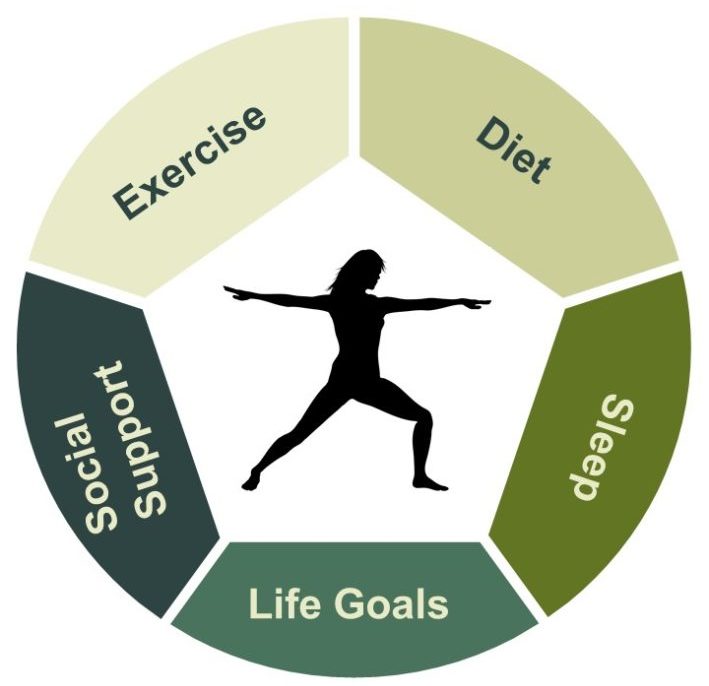

Based on these and other studies, we have identified five pillars of successful aging. We argue that these strategies are the foundation of a modern healthy lifestyle (Figure 1).

The five pillars of successful aging are regular physical activity, a healthy diet, regular high-quality sleep of at least seven hours duration a night, the selection and achievement of personally meaningful life goals, and a supportive social network. The central image was kindly provided by Vecteezy.

1. Exercise

Exercise is a fundamental strategy for successful aging 10.

Physical capabilities are maintained in individuals who are physically active throughout life 10-13. In fact, evidence suggests that exercise can delay the onset of physical frailty by up to 30 years 12. In addition, the benefits of exercise in maintaining cognitive function during aging are now well established 14-17.

For those not naturally inclined to exercise, there is good news. Even moderate exercise can provides positive protective effects towards the ravages of old age 18,19. Most compelling of all, even beginning to exercise later in life has benefits for successful aging 20. Further, exercise improves the health of older individuals suffering from age-related disability 21.

Thus, regular exercise is a powerful intervention to prevent or improve many of the conditions associated with old age.

2. Diet

Diets high in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, fish, nuts and vegetable oils have been shown to support successful aging.

For example, the now-famous Mediterranean diet, as well as similar diets such as the Portfolio Diet and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) help you maintain your physical, cognitive, and immune function into old age 10,22-26.

Key ingredients from these diets are especially important for successful aging. These include fish, vegetable oils such as olive oil, berries, spinach, grape, and berry products rich in polyphenols, walnuts, coffee, green tea, and lower-fat dairy products 10 27.

Intermittent Fasting

Individuals undergoing weight-loss dietary interventions also show improvements in vascular function, glucose-insulin regulation, memory function, and mobility 28,29.

Calorie restriction also provides advantages for successful aging over and above weight loss. Adults engaged in calorie restriction show preserved cardiovascular, immune, nervous system, and glucose-insulin function as they age 30-33.

Intermittent fasting, an increasingly popular method of calorie restriction, attenuates many of the negative effects of aging 32,34. This approach may have broader appeal as it is less draconian than traditional calorie-restriction methods 32,34.

It’s important to note that poorly executed or inappropriate calorie restrictions can do more harm than good 35,36. For these reasons, we suggest that you undertake calorie restriction in close collaboration with health professionals who are knowledgeable in the fields of nutrition and human performance.

3. Sleep

Healthy sleep provides essential support for all of your major physiological systems 37. Sleep is also crucial to maintain your key cognitive functions such as learning and memory, emotional regulation, attention, motivation, decision making, and motor control 37. As a result, sleep disturbances, especially chronic insomnia, have significant negative impacts on health and healthy aging.

All adults require healthy sleep for successful aging. Insomnia and other forms of sleep disturbance increase the risk of depression, infection, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all-cause mortality 37-40.

Disrupted sleep also plays a causal role in age-related cognitive decline and dementia, as well as being linked to the progression of both Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease 41-43.

Sadly the older we get, the more difficult it is to get a good night’s sleep 37. This is because insomnia is a common side effect of the aging process 37.

Fortunately, you can use low-risk interventions to successfully treat insomnia and insomnia-related health conditions 38,44. For example, cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness meditation, as well as mind-body relaxation methods such as exercise, Tai Chi, and Yoga can help you get a good night’s sleep 38,44.

4. Achievement of Life Goals

Exercise, diet, and sleep are all critical for successful aging. Yet, these interventions do not provide the meaning that makes life worth living. Furthermore, maintaining a meaningful life is challenging when faced with adversity and loss, which are inevitable occurrences during a long life.

To address this important issue, we have combined the Selective Optimisation with Compensation (SOC) framework 45 with Agile Methodology to create the SPAR framework. The purpose of SPAR is to help people achieve their personal life goals while maximizing gains and minimizing losses 45.

Importantly, the SPAR approach was specifically developed to help people achieve these goals in the face of change, adversity, and setbacks that are a natural, if unfortunate, part of life.

For more on the SPAR methodology, we refer you to our article that covers this approach in detail.

5. Develop and Maintain a Strong Social Support Network

Humans, as uniquely social beings, are naturally unsuited to isolation. Because of this, one of the best predictors of disease is social isolation or loneliness 46. The flip side is that people who enjoy high social well-being are more likely to experience healthy aging 47.

In fact, evidence suggests that your social support network may be the most important lifestyle factor of all for successful aging 47.

This is in part due to social genetic programs that are hard-wired in your DNA 52. The presence of these social genetic programs means that reaching out and helping other people is not only good for them, it’s also good for you 54. So why not take advantage of this genetic endowment and reconnect with family, friends, and colleagues?

The Five Pillars of Successful Aging Work Together

The five pillars of successful aging work by influencing interconnected and complex genetic, physiological, neural, and psychological networks. For these reasons, implementing lifestyle interventions across all pillars is far more effective than focusing on just one or two domains.

For example, combining diet and exercise is more efficacious than either diet or exercise alone 29. Optimal sleep improves exercise and exercise improves sleep 51. Sleep is required for optimal cognitive function in adults 37. Optimal cognition increases the probability of achieving your life goals and maintaining your social networks 47. This in turn reduces stress, helps you sleep, and improves the chance that you will exercise 37, 51.

Conclusion

The five pillars of successful aging provide simple and effective lifestyle interventions that improve your chances of living a long, healthy, and fulfilling life.

For more information, please download our FREE PDF guide to successful aging!

References and Further Reading

1 Riley, J. C. Rising life expectancy: a global history. (Cambridge University Press, 2001).

2 WHO. World health statistics 2015. (World Health Organization, 2015).

3 Rowe, J. W. & Kahn, R. L. Successful aging. The Gerontologist 37, 433-440 (1997).

4 Perls, T. T. in Brocklehurst’s Textbook of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology 184-187 (Elsevier, 2010).

5 Breslow, L. & Enstrom, J. E. Persistence of health habits and their relationship to mortality. Prev Med 9, 469-483 (1980).

6 Beeson, W. L., Mills, P. K., Phillips, R. L., Andress, M. & Fraser, G. E. Chronic disease among Seventh-day Adventists, a low-risk group. Rationale, methodology, and description of the population. Cancer 64 (1989).

7 Breslow, L. & Breslow, N. Health practices and disability: some evidence from Alameda County. Prev Med 22, 86-95 (1993).

8 Fraser, G. E. & Shavlik, D. J. Ten years of life: Is it a matter of choice? Arch Intern Med 161, 1645-1652 (2001).

9 Fraser, G. E., Cosgrove, C. M., Mashchak, A. D., Orlich, M. J. & Altekruse, S. F. Lower rates of cancer and all-cause mortality in an Adventist cohort compared with a US Census population. Cancer 126, 1102-1111 (2020).

10 Seals, D. R., Justice, J. N. & LaRocca, T. J. Physiological geroscience: targeting function to increase healthspan and achieve optimal longevity. J Physiol 594, 2001-2024 (2016).

11 Vogel, T. et al. Health benefits of physical activity in older patients: a review. Int J Clin Pract 63, 303-320 (2009).

12 Booth, F. W. & Zwetsloot, K. A. Basic concepts about genes, inactivity and aging. Scand J Med Sci Sports 20, 1-4 (2010).

13 Cunningham, C., O’ Sullivan, R., Caserotti, P. & Tully, M. A. Consequences of physical inactivity in older adults: A systematic review of reviews and meta-analyses. Scand J Med Sci Sports, 10.1111/sms.13616 (2020).

14 Colcombe, S. & Kramer, A. F. Fitness effects on the cognitive function of older adults: a meta-analytic study. Psychol Sci 14, 125-130 (2003).

15 Studenski, S. et al. From bedside to bench: does mental and physical activity promote cognitive vitality in late life? Sci Aging Knowledge Environ 2006, pe21-pe21 (2006).

16 Geda, Y. E. et al. Physical exercise, aging, and mild cognitive impairment: a population-based study. Arch Neurol 67, 80-86 (2010).

17 Northey, J. M., Cherbuin, N., Pumpa, K. L., Smee, D. J. & Rattray, B. Exercise interventions for cognitive function in adults older than 50: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 52 (2018).

18 Lee, I. M. & Paffenbarger, R. S., Jr. Associations of light, moderate, and vigorous intensity physical activity with longevity. The Harvard Alumni Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 151, 293-299 (2000).

19 Moore, S. C. et al. Leisure time physical activity of moderate to vigorous intensity and mortality: a large pooled cohort analysis. PLoS Med 9, e1001335-e1001335 (2012).

20 Paterson, D. H. & Warburton, D. E. Physical activity and functional limitations in older adults: a systematic review related to Canada’s Physical Activity Guidelines. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 7 (2010).

21 Fragala, M. S. et al. Resistance Training for Older Adults: Position Statement From the National Strength and Conditioning Association. J Strength Cond Res 33, 2019-2052 (2019).

22 Chiavaroli, L. et al. Portfolio Dietary Pattern and Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Controlled Trials. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 61, 43-53 (2018).

23 Serra-Majem, L. et al. Benefits of the Mediterranean diet: Epidemiological and molecular aspects. Molecular Aspects of Medicine 67, 1-55 (2019).

24 Kahleova, H. et al. Dietary Patterns and Cardiometabolic Outcomes in Diabetes: A Summary of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Nutrients 11, 2209 (2019).

25 Kargin, D., Tomaino, L. & Serra-Majem, L. Experimental Outcomes of the Mediterranean Diet: Lessons Learned from the Predimed Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 11, 2991 (2019).

26 Saulle, R., Lia, L., De Giusti, M. & La Torre, G. A systematic overview of the scientific literature on the association between Mediterranean Diet and the Stroke prevention. Clin Ter 170, e396-e408 (2019).

27 Cena, H. & Calder, P. C. Defining a Healthy Diet: Evidence for The Role of Contemporary Dietary Patterns in Health and Disease. Nutrients 12, E334 (2020).

28 Pierce, G. L. et al. Weight loss alone improves conduit and resistance artery endothelial function in young and older overweight/obese adults. Hypertension 52, 72-79, (2008).

29 Villareal, D. T. et al. Weight loss, exercise, or both and physical function in obese older adults. The New England journal of medicine 364, 1218-1229 (2011).

30 Weiss, E. P. & Fontana, L. Caloric restriction: powerful protection for the aging heart and vasculature. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301, H1205-H1219 (2011).

31 Stein, P. K. et al. Caloric restriction may reverse age-related autonomic decline in humans. Aging Cell 11, 644-650 (2012).

32 Rizza, W., Veronese, N. & Fontana, L. What are the roles of calorie restriction and diet quality in promoting healthy longevity? Ageing Res Rev 13, 38-45 (2014).

33 Kraus, W. E. et al. 2 years of calorie restriction and cardiometabolic risk (CALERIE): exploratory outcomes of a multicentre, phase 2, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 7, 673-683 (2019).

34 de Cabo, R. & Mattson, M. P. Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Health, Aging, and Disease. The New England journal of medicine 381, 2541-2551 (2019).

35 Locher, J. L. et al. Calorie restriction in overweight older adults: Do benefits exceed potential risks? Exp Gerontol 86, 4-13 (2016).

36 Papageorgiou, M., Kerschan-Schindl, K., Sathyapalan, T. & Pietschmann, P. Is Weight Loss Harmful for Skeletal Health in Obese Older Adults? Gerontology 66, 2-14 (2020).

37 Mander, B. A., Winer, J. R. & Walker, M. P. Sleep and Human Aging. Neuron 94, 19-36 (2017).

38 Irwin, M. R. Why Sleep Is Important for Health: A Psychoneuroimmunology Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 66, 143-172 (2015).

39 Fernandez-Mendoza, J., He, F., Vgontzas, A. N., Liao, D. & Bixler, E. O. Interplay of Objective Sleep Duration and Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Diseases on Cause-Specific Mortality. J Am Heart Assoc 8 (2019).

40 Fernandez-Mendoza, J. et al. Objective short sleep duration increases the risk of all-cause mortality associated with possible vascular cognitive impairment. Sleep Health 6, 71-78 (2020).

41 Mander, B. A., Winer, J. R. & Walker, M. P. A restless night makes for a rising tide of amyloid. Brain : a journal of neurology 140, 2066-2069 (2017).

42 Tsai, M.-S. et al. Risk of alzheimer’s disease in obstructive sleep apnea patients with or without treatment: Real-world evidence. Laryngoscope (2020).

43 Lloret, M.-A. et al. Is Sleep Disruption a Cause or Consequence of Alzheimer’s Disease? Reviewing Its Possible Role as a Biomarker. Int J Mol Sci 21, E1168 (2020).

44 Vanderlinden, J., Boen, F. & van Uffelen, J. G. Z. Effects of physical activity programs on sleep outcomes in older adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 17, 11-11 (2020).

45 Baltes, M. M. & Carstensen, L. L. The process of successful ageing. Ageing & Society 16, 397-422 (1996).

46 Cole, S. W. et al. Social regulation of gene expression in human leukocytes. Genome Biol 8 (2007).

47 Bosnes, I. et al. Lifestyle predictors of successful aging: A 20-year prospective HUNT study. PLoS One 14 (2019).

48 Kelly, M. E. et al. The impact of social activities, social networks, social support and social relationships on the cognitive functioning of healthy older adults: a systematic review. Syst Rev 6, 259-259 (2017).

49 Cole, S. W. The Conserved Transcriptional Response to Adversity. Curr Opin Behav Sci 28, 31-37 (2019).

50 Nelson-Coffey, S. K., Fritz, M. M., Lyubomirsky, S. & Cole, S. W. Kindness in the blood: A randomized controlled trial of the gene regulatory impact of prosocial behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology 81 (2017).

51 Dolezal, B. A., Neufeld, E. V., Boland, D. M., Martin, J. L. & Cooper, C. B. Interrelationship between Sleep and Exercise: A Systematic Review. Adv Prev Med 2017 (2017).

Disclaimer

The material displayed on this website is provided without any guarantees, conditions or warranties as to its accuracy.

Information written and expressed on this website is for education purposes and interest only. It is not intended to replace advice from your medical or healthcare professional.

You are encouraged to make your own health care choices based on your own research and in conjunction with your qualified practitioner.

The information provided on this website is not intended to provide a diagnosis, treatment or cure for any diseases. You should seek medical attention before undertaking any diet, exercise, other health program or other procedure described on this website.

To the fullest extent permitted by law we hereby expressly exclude all warranties and other terms which might otherwise be implied by statute, common law or the law of equity and must not be liable for any damages whatsoever, including but without limitation to any direct, indirect, special, consequential, punitive or incidental damages, or damages for loss of use, profits, data or other intangibles, damage to goodwill or reputation, injury or death, or the cost of procurement of substitute goods and services, arising out of or related to the use, inability to use, performance or failures of this website or any linked sites and any materials or information posted on those sites, irrespective of whether such damages were foreseeable or arise in contract, tort, equity, restitution, by statute, at common law or otherwise.

Ten Minutes is All You Need

Research has shown that ten minutes of moderate-to-vigorous exercise performed each day is enough to significantly reduce your risk of early death.

How to Find Significance in Life: Thriving in Solitude Part Three

Meaning in life research provides several behaviors and beliefs that can help you find significance in life.