Submaximal Training for Older Adults

“Success is the natural consequence of consistently applying basic fundamentals.”

― E. James Rohn

Performing heavy compound lifts such as squats, deadlifts and presses is an effective approach for increasing your bone density and improving your strength, power, and muscle mass. Thus, the aim of this program is for you to safely perform these fundamental barbell movements 2-3 times a week.

The Golden Rules of Lifting for Older Adults

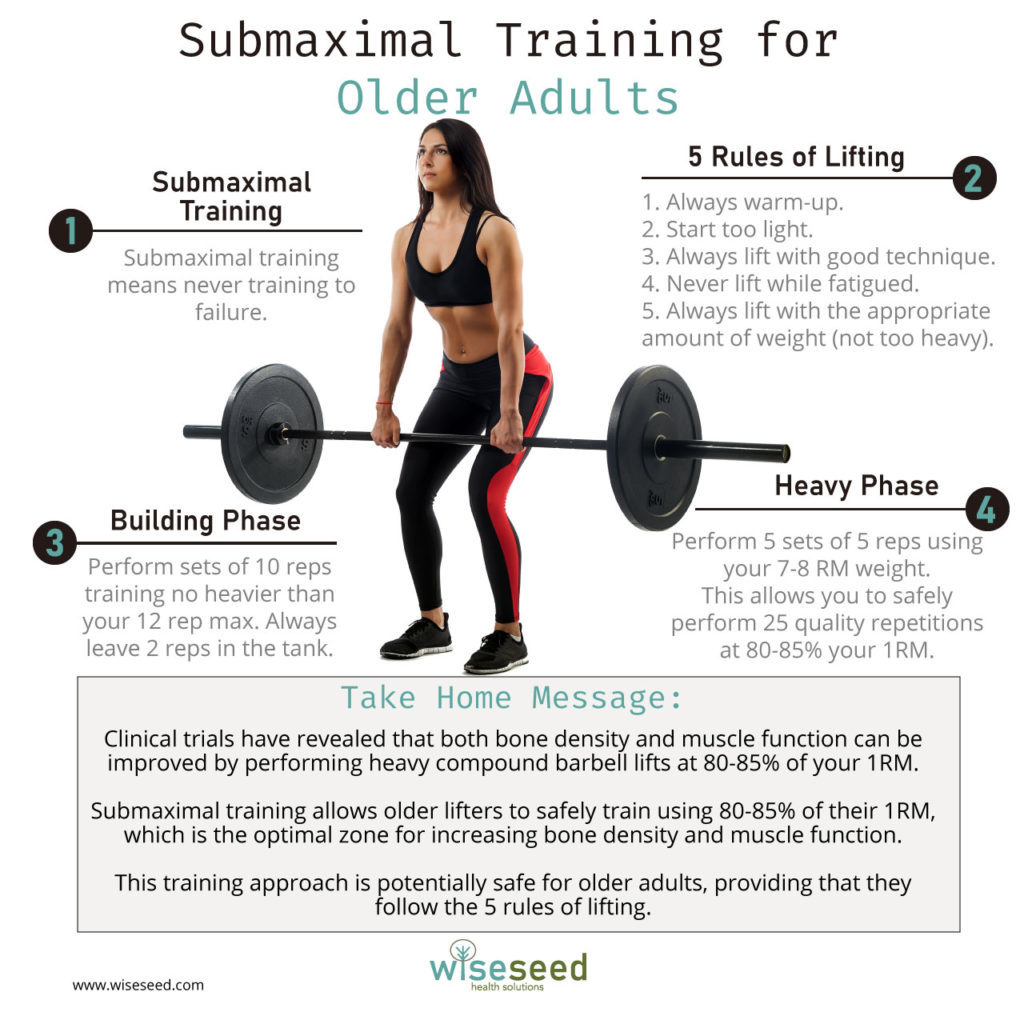

In my last article, I reviewed the training mistakes that, according to experienced lifters and strength athletes, account for most of their training-related injuries. These are (i) poor warm-up, (ii) poor lifting technique, (iii) lifting while fatigued, and (iv) using too heavy a weight.

These observations inspired five lifting rules older adults.

- Always perform an adequate warm-up.

- Start too light (a principle I learnt from Jim Wendler, a renowned strength and conditioning coach).

- Always lift with good technique.

- Never lift while fatigued.

- Always lift with the appropriate amount of weight (not too heavy).

What Is Submaximal Training?

Submaximal training simply means never training to failure. Combining submaximal training with a focus on appropriate bar speed and technique has several advantages for the older lifter. First and foremost, you greatly reduce your chance of getting injured. Second, because you are (or should) be using good technique for each-and-every lift, your technique will greatly improve over time. Finally, because you aren’t training in a fatigued state, you will recover faster and can therefore train more frequently.

Compound Exercises, Bone Density, and Physical Performance

The aim of this approach is for you to safely perform heavy compound barbell movements, twice a week. This is motivated by a series of high-quality clinical trials that show performing the deadlift, squat, shoulder press, bench-press and barbell row at greater than 80% of 1RM improves the bone density, muscle mass, and physical performance of older men and women (see (1-5)).

Core Barbell Exercises:

- Deadlift/Trap bar deadlift

- Squat

- Shoulder Press

- Bench Press

- Barbell Row

The participants in these clinical trials used Olympic weights and barbells to execute their lifts (1-5). This is because for performing heavy compounds lifts, barbells are best. Why? Because barbells can be loaded with heavy weights, lifted explosively with good technique, and the weight can be gradually increased as you get stronger.

However, if you have joint or mobility issues that rule our barbell lifts, you can use machines such as the leg press, chest press, rows, and shoulder press. If you do use machines, please make sure that you set up and use the machine within a safe range of motion. For example, the 45-degree leg press is notorious for rupturing discs in the lower back. This generally occurs when people use too heavy a weight and round their lower back at the bottom position of the press.

And also remember that the rules of lifting and progressive overload remain the same whether you use machines or barbells. If you are using machines, you still need to warm up, you still need to start too light, you should not lift when fatigued, and you must use the appropriate weight for your level of strength and conditioning.

How Repetition Number Relates to your 1RM

The sole purpose of this program is to allow you to safely train within 80-85% of your 1RM.

Table One shows how different maximum repetition numbers correlate to your 1 rep max. Although this is an approximation, it provides a reasonable guide for you to understand the repetition scheme that underpins this program.

From table one, we can see that your 6-8 rep max lies within 80-85% of your 1RM. Thus, by performing five sets consisting of five repetitions using your 7-8RM weight, you are performing 25 high-quality repetitions within the optimal training zone for improving both bone density and muscle function (1-5).

[ninja_tables id=”33380″]

Table One. How the weights of your repetition maximums relate to as a percentage to your one repetition maximum weight. For example, the weight you can lift for a maximum of eight repetitions represents approximately 80% of your one rep max.

Progression

The heart and soul of progressive resistance training is progression. What is progression? Simple: increasing either the weight that you lift and/or the number of repetitions that you perform over time.

While this is an easy concept to understand, the challenge is knowing when and how much weight you should add to maximize your strength without getting injured or stalling.

Focus

In my opinion, you should focus on just two things during their first three months of lifting. First, learning good lifting technique. This includes learning how to accelerate the bar throughout the lift. Second, accumulating training volume. And by training volume I mean training consistently (i.e., lifting 2-3 times a week) using good technique.

I recommend starting too light. Starting too light allows you to learn and practice good lifting technique without getting hurt, while giving your body time to adapt to the new stress of training. Another reason why starting out too light is so important is that it teaches you how to lift explosively, yet with control.

Once your technique is on point and you have adapted to weight training, your training focus shifts to performing five sets of five high-quality repetitions at around 80% of your 1RM.

Lifting Technique

Using proper lifting technique is mandatory. For learning proper lifting technique, you can’t beat having a good coach. While you can certainly teach yourself how to squat and deadlift, a good coach will save you time and will prevent you from developing bad habits that could lead to injury when the weights get heavier.

Alternatively, you can learn from online coaches, and monitor and adjust your form by videoing yourself while lifting. No matter which of these approaches you choose, dialing in good lifting technique will take you a few months.

Why does it take so long? Using squats as an example, you will need to experiment with foot position, bar position, squatting depth, and bar speed to find the optimal squatting configuration for your structure and mobility. Then, you must practice good lifting technique enough times to encode the new movement pattern. Unfortunately, this takes time and consistent effort.

Workout Structure

Phase I: The First Three Months

For the first three months of lifting, your goal is to perfect your technique and adapt to regular training. You must start using light weights that allow you to easily perform three sets of ten repetitions. This is critically important!

A recommended beginner’s template is shown in Table Two.

[ninja_tables id=”33385″]

Table Two. A simple training template for beginners or those returning from injury. The focus is on learning and practicing lifting technique and accumulating quality training volume.

Start by training two days a week, for example Monday and Thursday. Once you have adapted to a twice-weekly workload, you can add a third workout each week. For example, train Monday, Wednesday and Friday alternating between workout A and workout B.

For the impact training, start at the easiest variations and gradually progress over time. Think of impact training as an extension of your warm-up, not an epic undertaking. For impact training, program conservatively and be consistent.

Some upper body impact progressions can be viewed here.

Some lower body impact progressions can be viewed here.

Phase II

After Three Months, you will switch to the 5×5 repetition scheme shown in Table Three.

[ninja_tables id=”33388″]

Table Three. Five by Five Heavy Lifting Program. Here the focus is on safely lifting 80-85% of your 1RM for five sets of five repetitions.

Adding Weight

Version One

You decide whether to add more weight depending on how you felt during the lifts. This is the simplest way to progress.

The success of this approach depends on how well you understand bar speed. If you really understand bar speed, then this approach works very well. In contrast, if you don’t understand bar speed, then this approach won’t work.

The caveat here is that as the load gets heavier, the bar will obviously get slower. However, your lifts should still feel crisp, smooth, and controlled. If this is the case, add more weight. In contrast, if you had to grind out reps, then don’t add more weight.

Using this approach, when you transition from Phase I to Phase II, don’t change the weight. You only change the rep scheme. What should happen is that the weights that were challenging at the end of Phase I feel light and explosive when lifting in the 5-rep range. Thus, you are starting Phase II too light.

Version Two

If you are looking for a more objective way to gauge progression, this approach may work for you.

Phase I

During Phase I, your goals are perfecting your technique and adapting to training consistently.

While training within the 10-rep range, you want to stay at or below your 12RM. Therefore, on your last set, try and hit 12 reps. If you hit 12 reps with good form, add weight. If you struggle to complete 12 reps, don’t add weight.

Phase II

During this phase, you are aiming to perform five sets of five at around your 7-8RM. This means you will be performing 25 high quality reps at 80-85% of your 1RM for each lift. To determine if it’s time to add weight, try and perform eight quality reps out on your last set. If the eight rep was of high quality, add weight. If it was a grinder, don’t add weight.

Table Four summarizes the rep schemes for both phases, using three compound movements. The basic idea is that if you hit all your reps using good form, you can add weight.

[ninja_tables id=”33390″]

Table Four. Repetition goals for assessing when to add weight to the bar during the 3 x 10 phase (Phase I) and the 5 x 5 phase (Phase II).

How Much Weight Should You Add?

In Phase I when you are starting out light, you should experience reasonably rapid improvements in strength as you dial in your technique and your lifts become more efficient. Here, adding 2.5 kg each week (i.e., 1.25 kg a side) is likely fine.

Ideally you would perfectly match your increase in weight to your increase in strength. The problem is that muscle adaptation is both slow and variable, especially for older adults. Thus, you are far more likely to over-shoot and add too much weight.

For this reason when you start training in the 80-85% zone, you want to add as little weight as possible with each increment. This will reduce the chance of you adding too much weight and stalling or worse, getting injured. Note that this is especially true for bench press, and even more so for shoulder press, both of which can be extremely slow to improve (particularly for women).

One option is to purchase a set of Olympic weights that range from 0.25 kg up 2 kg. These mini-plates let you add as little as 0.5 kg to the bar with each progression.

What Do You Do When You Stop Improving?

Sooner or later, you are going to hit the point where you just can’t safely add more weight.

Here, the simplest solution is to calculate 0.85 of your current weight and simply reset your training weight to that number. For example, if you stop progressing your squats at 100 kg, then multiply 100 x 0.85, which gives you 85 kg. Go back to squatting at 85 kg and work your way back up to 100 kg.

Hopefully, you will break through the 100 kg barrier and hit a new plateau. In lifting, you often must take two steps back to take three steps forward.

Keep in mind that different lifts will likely stall at different rates. If this happens, simply reset your stalled lifts while keeping your others lifts moving forward.

Finally, there will come a time when you reach your limit with this type of simple programming. You can decide to simply maintain your current level of strength and work on other aspects of fitness. Alternatively, if you wish to keep getting stronger, then it’s time for you to initiate a more sophisticated training program that can bring you closer to realizing your genetic strength potential.

Take Home Message

Clinical trials have revealed that both bone density and muscle function can be improved by performing heavy compound barbell lifts twice a week at 80-85% of your 1RM.

Submaximal training is one approach for older lifters to safely train within their 80-85% 1RM range.

This training approach is potentially safe for older adults, providing that they also follow the 5 rules of lifting.

Please click on the link below for your free PDF.

References and Further Reading

1. S. L. Watson, B. K. Weeks, L. J. Weis, S. A. Horan, B. R. Beck, Heavy resistance training is safe and improves bone, function, and stature in postmenopausal women with low to very low bone mass: novel early findings from the LIFTMOR trial. Osteoporos Int 26, 2889-2894 (2015).

2. S. L. Watson et al., High-Intensity Resistance and Impact Training Improves Bone Mineral Density and Physical Function in Postmenopausal Women With Osteopenia and Osteoporosis: The LIFTMOR Randomized Controlled Trial. J Bone Miner Res 33, 211-220 (2018).

3. A. T. Harding et al., Effects of supervised high-intensity resistance and impact training or machine-based isometric training on regional bone geometry and strength in middle-aged and older men with low bone mass: The LIFTMOR-M semi-randomised controlled trial. Bone 136, 115362 (2020).

4. A. T. Harding et al., A Comparison of Bone-Targeted Exercise Strategies to Reduce Fracture Risk in Middle-Aged and Older Men with Osteopenia and Osteoporosis: LIFTMOR-M Semi-Randomized Controlled Trial. J Bone Miner Res 35, 1404-1414 (2020).

5. C. Lambert, B. R. Beck, A. T. Harding, S. L. Watson, B. K. Weeks, Regional changes in indices of bone strength of upper and lower limbs in response to high-intensity impact loading or high-intensity resistance training. Bone 132, 115192 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Images provided by Vitalij Sova and FlamingoImages

Disclaimer

The material displayed on this website is provided without any guarantees, conditions or warranties as to its accuracy.

Information written and expressed on this website is for education purposes and interest only. It is not intended to replace advice from your medical or healthcare professional.

You are encouraged to make your own health care choices based on your own research and in conjunction with your qualified practitioner.

The information provided on this website is not intended to provide a diagnosis, treatment or cure for any diseases. You should seek medical attention before undertaking any diet, exercise, other health program or other procedure described on this website.

To the fullest extent permitted by law we hereby expressly exclude all warranties and other terms which might otherwise be implied by statute, common law or the law of equity and must not be liable for any damages whatsoever, including but without limitation to any direct, indirect, special, consequential, punitive or incidental damages, or damages for loss of use, profits, data or other intangibles, damage to goodwill or reputation, injury or death, or the cost of procurement of substitute goods and services, arising out of or related to the use, inability to use, performance or failures of this website or any linked sites and any materials or information posted on those sites, irrespective of whether such damages were foreseeable or arise in contract, tort, equity, restitution, by statute, at common law or otherwise.

Ten Minutes is All You Need

Research has shown that ten minutes of moderate-to-vigorous exercise performed each day is enough to significantly reduce your risk of early death.

Thriving in Solitude: Making Sense of Your Life

When you are self-aware and your values and actions are aligned, life makes sense. As a result, you have a more positive outlook, you feel authentic, and you are on the path to meaning.