Six Ways to Preserve Cognitive Function

Take Home Message

– Steady cognitive decline is considered to be a normal part of the aging process

– However, recent studies have identified groups of older adults who maintain a very-high cognitive function

– Further, studies that measure the biological age of the human brain have identified individuals whose brains are much younger compared to their chronological age

– Collectively, these findings challenge the long-standing paradigm that steady cognitive decline is an inevitable part of the aging process

Cognitive decline, aging and the puzzle of old CEOs

Cognitive decline has long been thought to be an unfortunate yet inevitable part of the normal aging process. This is best illustrated in the fields of mathematics, physics, chemistry, and science. These professions rely heavily on complex problem solving (fluid intelligence) and memory, which are the two domains that are most heavily impacted by age. The career productivity of scientists and mathematicians’ peaks in their early 20’s and then steadily declines with age.

Paradoxically, this phenomenon is not observed for CEOs. Although CEOs must be proficient at complex problem solving, the average age of CEOs peaks at around 60 years of age, which is well past the professional peak of mathematicians and scientists (1).

Historically, it has been argued that the late-fifties is the ‘sweet spot’ between having developed sufficient professional expertise, built the necessary professional networks and acquired emotional control while still maintaining enough fluid intelligence to effectively run large, complex organisations (1).

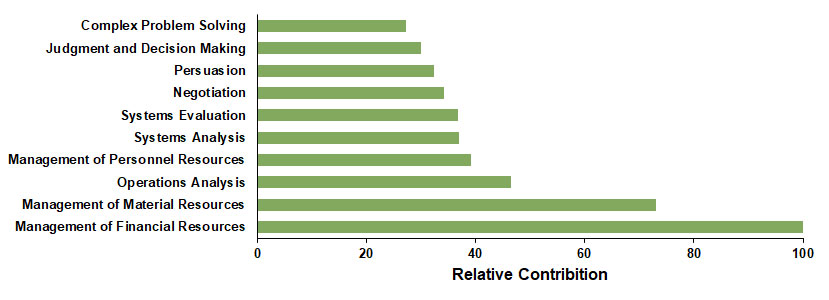

However, many of the skills that distinguish CEO’s from other professionals rely heavily on the cognitive functions that are most susceptible to age-related decline (Figure 1). This suggests that successful CEO’s still possess large reserves of fluid intelligence and working memory despite being well ‘past their prime’ with respect to cognition.

Is it possible to preserve cognitive function and perform at the highest cognitive level despite being old?

Some people preserve high cognitive function into old age.

Historic studies measuring cognitive decline consist of cross-sectional studies that compare the average intelligence of groups of people of different ages. These analyses reveal that the aggregate cognitive function steadily declines as the population gets older.

In our last article, we explored the effects of age-related cognitive decline on performance and provided strategies to help you overcome your cognitive limitations.

Although strategies that compensate for our declining intelligence are important, it would be much better if we could also preserve our cognitive powers throughout our lives.

Intriguingly, recent studies that follow individual cognitive function over time have identified a more nuanced pattern of age-related cognitive decline. These findings challenge the notion that steady cognitive decline is an inevitable consequence of growing old.

Study One: Mella et al

The first study followed cognitive change over a seven-year period, relying solely on individual data gathered over the duration of the study. Cognitive domains measured included working memory, simple reaction times, processing speed and fluid intelligence (2). The largest proportion of individuals showed cognitive decline (2). This finding is entirely consistent with the raft of historic retrospective studies showing that cognition steadily declines with age. However, a surprisingly large proportion of participants (between 35% and 50%) showed stability or even improvement in cognition over the seven-year period (2).

The observation that more than a third of individuals maintained or even improved their cognition (2), suggests that historical aging studies, even those using a longitudinal design, may have overestimated the rate of age-related cognitive decline (2).

Study Two: Zammet et al

The idea that cognitive decline is highly variable between individuals is further supported by the Einstein Aging Study (EAS). This study followed a large population of older adults with diverse ethnic, educational, occupational, and socio-economic backgrounds, health-status, and cognitive functions (3). The EAS sought to identify subgroups of adults based on cognitive performance using ten different neurocognitive tests (3).

| Cognitive Class | Percentage (%) |

| Disadvantaged | 5.7 |

| Poor Language | 6.7 |

| Poor episodic memory and fluency | 6.0 |

| Poor processing speed and executive function | 6.1 |

| Poor executive and poor working memory | 2.5 |

| Low average | 25.7 |

| Average | 32.7 |

| High Average | 10.1 |

| Elite | 7.7 |

The EAS identified nine different cognitive classes, as shown in Table 1. The take home message for us is that over 50% of all participants displayed average or above average cognitive function (3). Importantly, around 18% of participants maintained a high-average to elite level of cognitive function throughout the period of testing (3).

Study Three: Casaletto et al

The third and most recent study followed the cognitive function of 314 functionally normal adults, with a mean age of 69 years, over a period of two years (4). Encouragingly, only 29 individuals displayed declining cognitive speed, and only 50 individuals had declining memory (4). Importantly, a mere 2.5% of the cohort experienced both declining speed and declining memory (4).

Those individuals who displayed a loss in cognitive speed were of greater age, had higher levels of inflammation and experienced more cognitive complaints compared with cognitively stable adults (4). In contrast, individuals who displayed declining memory were more likely to be male and had lower depressive symptoms, and lower grey matter volumes and white matter hyperintensities compared with memory-stable adults (4). These data suggest that declining speed versus declining memory represent two separate aging phenotypes, with different underlying mechanisms (4).

For us, the most important finding is that most of the study participants had high cognition that did not decline over the two-year study (4). This is despite the fact that the study cohort was comprised of old to very-old individuals (4).

Preserving cognitive function is indeed possible

Collectively, these three studies all show that the rate of cognitive decline is highly variable between individuals (2-4). This finding has two important implications for those of us who care about preserving our brain function.

First, historical cognitive decline measurements using the aggregate may have over-estimated the rate of age-related cognitive decline. This is because the average is skewed by individuals experiencing rapid rates of decline (2).

Second, all three studies identified adults who did not experience any measurable cognitive decline over the duration of the study. In fact, two of the studies identified older adults who retain high to very-high cognitive function despite being old (3, 4).

People’s brains do not age at the same rate

The studies examined above show us that there exists a large variation between the degree of cognitive decline experienced by different people as they age. Further, there appears to be a lucky group of individuals who preserve high cognitive function even into old age. Could this be because people’s brains age at different rates?

While we have known for decades that cognition declines with age, exactly how our brains age has been a mystery. This changed recently when researchers began combining advanced imaging techniques with machine learning, allowing them to measure the biological age of the human brain, the so called brainAGE (5, 6).

The striking finding from these studies is that BrainAge can vary considerably from chronological age. For example, in the Dunedin Study, a population-representative the 1972–73 birth cohort, brainAGE ranged from 24 to 72 years, despite everyone studied being 45 years old (7)!

These and other data clearly demonstrate that some lucky individuals have brains that are biologically much younger than their chronological age.

So, why do brains age at different rates?

The role of Genetics and Early Life Factors

We all know that genes drive our biology, and the brain is certainly no exception to this rule. This was demonstrated in studies performed in twins, which indicate that brainAGE is a moderately heritable phenotype (8). This may help explain why early deficits in brain structure correlate with a life-long effects on cognitive function (7).

Additional factors outside of our control also effect brain development. For example, conditions experienced by the embryo within the Mother’s womb during pregnancy (e.g. exposure to smoking, alcohol or other chemicals, injury or illness) shape our brain development (7). In addition, very early childhood events, such as experiencing nutritional deficits, illness and injury also contribute to some of the observed life-long variance in human brain structure and function (7).

Thus, both your genes and early life events influence your brain development and structure. This in turn determines your cognitive function and influences the rate at which your brain ages over time.

Lifestyle

Thankfully, brainAGE is not all in the genes. Although brainAGE is certainly influenced by your genetics and early childhood events, studies are beginning to identify lifestyle choices that also have a significant part to play in how your brain ages.

In fact, several lifestyle factors have been shown to increase brainAGE. For example, obesity increases the risk of neurodegeneration within the general population and is associated with a greater degree of cerebral white matter atrophy (9). During middle-age, white matter atrophy caused by obesity corresponds to an increase of brain age of roughly 10 years (9). Other factors such as smoking, regular consumption of alcohol also increases brainAGE relative to chronological age (10). Thus obesity, smoking and alcohol consumption all hasten the aging process of the brain.

On the other side of the ledger, old adults possessing high cardiorespiratory fitness preserve their grey and white matter integrity in areas related to memory and information processing (11, 12). In addition, education and physical activity are both associated with a younger brainAGE relative to chronological age (13). Further, long-term meditation has been linked to improvements in brainAGE (14).

Collectively, these studies show that lifestyle choices may have a dramatic effect on how your brain ages.

Conclusion: it may be possible to preserve high cognitive function throughout life.

Historically, steady cognitive decline has been accepted as an inevitable component of ‘normal aging’. Now, the combined data from the brainAGE and cognitive function studies show that both brain structural decline and cognitive decline are highly variable between individuals.

Importantly, the brainAGE studies show that a small number of people maintain a young brain relative to their chronological age. Consistent with this observation, recent cognition studies have revealed groups of older adults who maintain a very-high cognitive function despite being old. These two findings challenge the paradigm that cognitive decline is an inevitable consequence of old age.

We think that this phenomenon may explain how CEO’s can effectively manage large, complex organisations despite being ‘old’. We hypothesise that the selection process for CEO’s naturally favours older people who have developed extensive business acumen, which takes time. However, we predict that the CEO selection process favours those experienced, older candidates who have also maintained a very-high cognitive function and a young brainAGE.

The good news for you is that simple lifestyle interventions may reduce or delay age-related cognitive decline.

Staying lean, avoiding smoking and alcohol, maintaining cardio-respiratory fitness, becoming educated and staying a life-long learner, and meditation have all been shown to help keep your brain young.

References and Further Reading

1. T. Salthouse, Consequences of age-related cognitive declines. Annu Rev Psychol 63, 201-226 (2012).

2. N. Mella, D. Fagot, O. Renaud, M. Kliegel, A. De Ribaupierre, Individual differences in developmental change: Quantifying the amplitude and heterogeneity in cognitive change across old age. Journal of Intelligence 6, 10 (2018).

3. A. R. Zammit, C. B. Hall, R. B. Lipton, M. J. Katz, G. Muniz-Terrera, Identification of Heterogeneous Cognitive Subgroups in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Latent Class Analysis of the Einstein Aging Study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 24, 511-523 (2018).

4. K. B. Casaletto et al., Cognitive aging is not created equally: differentiating unique cognitive phenotypes in “normal” adults. Neurobiology of Aging 77, 13-19 (2019).

5. K. Franke, G. Ziegler, S. Kloppel, C. Gaser, I. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging, Estimating the age of healthy subjects from T1-weighted MRI scans using kernel methods: exploring the influence of various parameters. Neuroimage 50, 883-892 (2010).

6. N. M. Ashpole et al., IGF-1 has sexually dimorphic, pleiotropic, and time-dependent effects on healthspan, pathology, and lifespan. Geroscience 39, 129-145 (2017).

7. M. L. Elliott et al., Brain-age in midlife is associated with accelerated biological aging and cognitive decline in a longitudinal birth cohort. Mol Psychiatry, (2019).

8. J. H. Cole et al., Predicting brain age with deep learning from raw imaging data results in a reliable and heritable biomarker. Neuroimage 163, 115-124 (2017).

9. L. Ronan et al., Obesity associated with increased brain age from midlife. Neurobiol Aging 47, 63-70 (2016).

10. K. Ning, L. Zhao, W. Matloff, F. Sun, A. W. Toga, Association of relative brain age with tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, and genetic variants. Sci Rep 10, 10 (2020).

11. A. Z. Burzynska et al., White matter integrity, hippocampal volume, and cognitive performance of a world-famous nonagenarian track-and-field athlete. Neurocase 22, 135-144 (2016).

12. K. Ding et al., Cardiorespiratory Fitness and White Matter Neuronal Fiber Integrity in Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 61, 729-739 (2018).

13. J. Steffener et al., Differences between chronological and brain age are related to education and self-reported physical activity. Neurobiol Aging 40, 138-144 (2016).

14. E. Luders, N. Cherbuin, C. Gaser, Estimating brain age using high-resolution pattern recognition: Younger brains in long-term meditation practitioners. Neuroimage134, 508-513 (2016).

Disclaimer

The material displayed on this website is provided without any guarantees, conditions or warranties as to its accuracy.

Information written and expressed on this website is for education purposes and interest only. It is not intended to replace advice from your medical or healthcare professional.

You are encouraged to make your own health care choices based on your own research and in conjunction with your qualified practitioner.

The information provided on this website is not intended to provide a diagnosis, treatment or cure for any diseases. You should seek medical attention before undertaking any diet, exercise, other health program or other procedure described on this website.

To the fullest extent permitted by law we hereby expressly exclude all warranties and other terms which might otherwise be implied by statute, common law or the law of equity and must not be liable for any damages whatsoever, including but without limitation to any direct, indirect, special, consequential, punitive or incidental damages, or damages for loss of use, profits, data or other intangibles, damage to goodwill or reputation, injury or death, or the cost of procurement of substitute goods and services, arising out of or related to the use, inability to use, performance or failures of this website or any linked sites and any materials or information posted on those sites, irrespective of whether such damages were foreseeable or arise in contract, tort, equity, restitution, by statute, at common law or otherwise.

Ten Minutes is All You Need

Research has shown that ten minutes of moderate-to-vigorous exercise performed each day is enough to significantly reduce your risk of early death.

How to Improve Cognitive Functions

The latest research suggests that by improving your cognitive functions through training, you can become more resilient and increase your chance living a meaningful life.