How to Perform Efficient Strength Workouts

“The key is in not spending time, but in investing it.

“

– Stephen R. Covey.

We all know we should work-out regularly for optimal health. The problem is finding the time to train. For many people, squeezing in workouts around demanding careers, family commitments and study can be almost impossible.

Fortunately for us, a recent publication Dr Iversen and Colleagues reviews the key principles for designing short workouts that improve your strength and body composition (1).

1. Training Volume

The available evidence suggests that your total weekly training volume is the most important variable for your training success.

While it’s true that people training for maximal strength and size must train more frequently than once a week, training a muscle group once a week is sufficient to produce significant increases in both strength and size (2, 3). Thus, for those of you who have limited time to train, your focus should be on achieving the volume required to increase your strength and muscle mass, not on how often you train.

What is the minimum required volume to increase your strength and muscle mass?

The current consensus is that 4-12 sets per muscle group per week is optimal for increasing your strength and size (4). However, recent studies have shown that performing a single heavy working set 3 times a week is sufficient for increasing your strength, which equates to just three working sets per week (5, 6). Because there remains some uncertainty around the actual minimum effective dose (7), the Author’s recommend performing at least 4 working sets per week for each major muscle group (1).

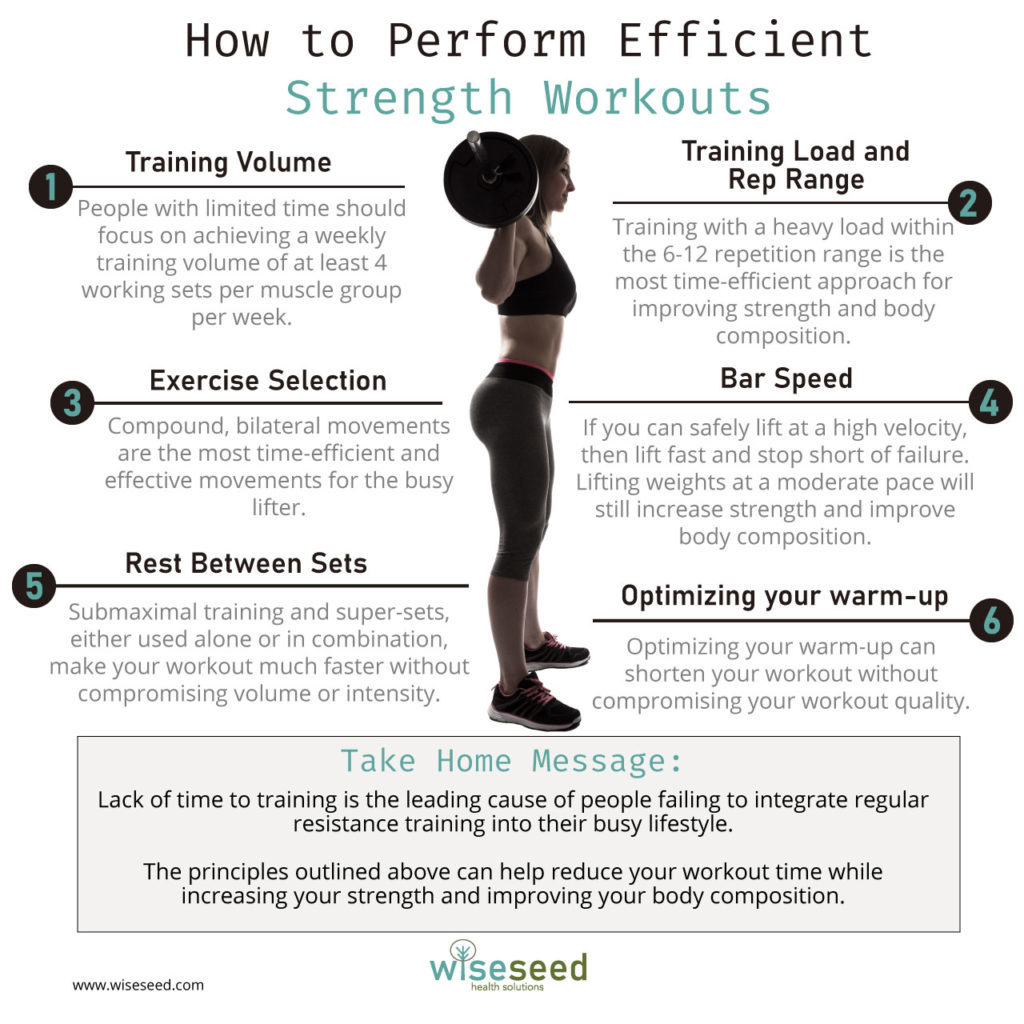

Conclusion: People with limited time should focus on achieving their weekly training volume. Because there remains uncertainty as to minimum effective training volume, perform at least 4 working sets per muscle group per week.

2. Training Load and Repetition Range

Training with either heavy loads or lighter loads can increase muscle mass and improve strength (1). However, training with heavier loads is recommended for the following reasons. First, you can increase your strength and body composition using fewer repetitions using a heavy load (1). Second, training with a heavy load means that you don’t have to train to failure to get results.

The vast body of evidence supports repetitions within the 6-12 repetition range is optimal for increasing both strength and muscle mass (8). Therefore, you should stick within this repetition range for most of your training.

Conclusion: Training with a heavy load within the 6-12 repetition range is the most time-efficient approach for improving strength and body composition.

3. Exercise Selection

Compound versus isolation movements

Compound exercises include exercises such as squats, deadlifts, bench press and rows. These multi-joint exercises have the advantages of activating multiple muscle groups while allowing you to lift heavier weights. Further, people using training programs that utilize compound movements gain strength faster and ultimately become much stronger than people who use programs that focus on single-joint exercises such as bicep curls and leg extensions (9). Thus, compound movements are the exercise of choice for the time-poor lifter.

Free-weights versus machines

Obviously, you can perform compound movements using a variety of tools. The strength gained from machines versus free weights appears to be approximately the same (10). Therefore, pick whichever approach you prefer based on availability, safety, your mobility, and your personal preference.

Dumbbells versus barbells

Dumbbells allow you to lift weights with a greater range of motion compared to barbells, which can benefit lifters with mobility issues. That said, barbells are the superior choice for the time-poor lifter because barbells allow you to lift heavier weights with greater muscle activation compared to dumbbells (11). Thus, unless mobility issues dictate otherwise, train with barbells.

Bilateral versus Unilateral

Bilateral simply means training both sides of the body at the same time, whereas unilateral means training one side of the body at a time. For example, squatting is a bilateral lower body exercise because squats train both legs simultaneously, whereas lunges are a unilateral lower-body exercise because they work one leg at a time.

Research has shown that both forms of training produce comparable increases in strength and muscle mass (1). Nevertheless, when you are facing significant time constraints, bilateral exercises win out for one simple reason: They take half the time to complete because both sides of the body are trained simultaneously.

Conclusion: Compound, bilateral movements such as bench press, shoulder press, rows, pull-ups, squats, and deadlifts are the most time-efficient and effective movements for the busy lifter. Either free-weights or machines can be used. If using free weights, barbells are the optimal lifting tool.

4. Bar Speed

In terms of training economy, moving the bar fast simultaneously trains both strength and power. As a bonus, you complete each set faster, and because you don’t train in a fatigued state, your rest periods can also be shortened.

The importance of bar speed combined with submaximal training is supported by research. For example, one study compared lifters who performed every repetition at a fast velocity and stopped lifting when the bar speed declined (the maximal velocity group), to a second group that lifted at their normal pace and trained to failure (the traditional group).

At the end of the study, the maximal velocity group performed 62% fewer repetitions than the traditional group (12). Despite this dramatic reduction in volume, the maximal velocity group improved their 1RM by 10%, whereas the traditional group improved their 1RM by less than 1% (12)! Thus, bar speed can make a big difference to your physical performance.

What if I can’t lift fast?

However, not everyone is a naturally fast lifter. If this is you, take comfort in the fact that training at moderate repetition speeds also makes you strong. In addition, training at a slower speed increases your time-under-tension, which stimulates muscle growth.

Conclusion: If you can safely lift at a high velocity, then lift fast and stop short of failure. If you aren’t a naturally explosive lifter, not to worry. You will still experience increases in strength and muscle mass when lifting weights at a moderate pace. In this scenario, consider taking your last working set close to failure.

5. Rest Between Sets

Adequate rest between sets is essential for optimizing gains in strength and size from resistance training. Current recommendations are to rest 3–5 min between sets when training to maximize strength, 1–2 minutes between sets when the goal is maximal muscle growth, and a 30–60 s rest interval when the goal is to maximize muscular endurance (4).

Although there is precedent for reducing rest periods while maintaining strength and size gains, this is dependent on the training experience of individuals tested. For beginners, rest periods of 1-2 minutes between sets are recommended. Experienced lifters require rest periods of greater than 2 minutes between sets (13). For reasons of safety, it’s better to rest longer and lift in a fresh state than to rush through your workout and risk injury.

Submaximal Training and Supersets

One advantage of submaximal training because you don’t train to failure. Therefore, you are accumulating far less fatigue during your workouts, which allows you to safely reduce rest periods between sets. This means shorter workouts without sacrificing either volume or intensity.

Another option that can significantly reduce your workout time is to use supersets. Supersets simply means performing two or more exercise in quick succession, with little or no rest between each exercise (4). It’s best to perform supersets using exercises that target opposing muscle groups of the upper body (4).

For example, super-setting bench press with barbell rows is an effective approach that has been shown to produce the same gains in strength and power in half the time. In this example, you would perform one set of bench-press, then immediately perform one set of rows, followed by two minutes rest. That’s one super-set. Repeat 2-3 times.

I don’t recommend super-setting lower body exercises. This is because super-setting can fatigue stabilizing muscles, which may compromise your stability, technique, and safety for lower body compound lifts such as the squat and deadlift.

Conclusion: Submaximal training and super-sets, either used alone or in combination, can significantly reduce rest periods and make your workout much faster without compromising volume or intensity.

6. Optimizing your warm-up

Performing an adequate warm-up is essential for safe lifting and is therefore mandatory, especially for older lifters. However, unless you are specifically training to improve mobility and flexibility, you can greatly reduce your warm-up time by making your warm-up specific for the lifts in your workout (4).

To avoid injury, I recommend always performing a 5-minute general body warm-up, for example calisthenics performed at a steady pace or performing some light aerobics. However, you then only perform warm-ups that are specific to the exercises you are performing. Taking squats as an example, you could perform a set of bodyweight squats, a set with the empty bar, and then two intermediate weighted squat warm-ups before hitting your working sets. The idea is to use shortest number of warm-up sets required to safely perform your working sets.

Conclusion: Optimizing your warm-up so that it’s specific to your workout can shave considerable time off your training schedule without compromising your workout quality.

Putting it all-together

This is a simple and most time-efficient workout structure to increase your strength and muscle mass in minimal time.

Obviously, you’ll need to train longer, more often and with more variation if you want to realize your true genetic potential. However, it should get the job done when you have limited time to train.

I’ve included two workouts. If possible, I recommend training twice a week. If not, perform workout A one week followed by workout B the next week. It would be beneficial if you also perform some form of conditioning during each week, with interval training being the most time-efficient option available.

Workout A

- 5-minute general body warm-up

- Barbell Squat 4 sets of 6-12 reps

- Barbell Bench Press 4 sets of 6-12 reps: super-set with

- Barbell Row 4 sets of 6-12 reps

Optional

- Core Exercise (e.g. plank) 3 sets of 30-60 seconds: super-set with

- Calves (e.g. calf raises) 3 sets of 10-20 reps

Workout B

- 5-minute general body warm-up

- Trap Bar Deadlift 4 sets of 6-12 reps

- Seated Barbell Shoulder Press 4 sets of 6-12 reps: super-set with

- Pull-ups/lat pull-down 4 sets of 6-12 reps

Optional

- Core Exercise (e.g. plank) 3 sets of 30-60 seconds: super-set with

- Calves (e.g. calf raises) 3 sets of 10-20 reps

Take Home Message

Lack of time to training is the leading cause of people failing to integrate regular resistance training into their lifestyle. If this applies to you, then the principles outlined here should help reduce your workout time while still increasing your strength and improving your body composition.

Please click on the link below to download your free PDF.

References and Further Reading

1. V. M. Iversen, M. Norum, B. J. Schoenfeld, M. S. Fimland, No Time to Lift? Designing Time-Efficient Training Programs for Strength and Hypertrophy: A Narrative Review. Sports Medicine, 1-17 (2021).

2. G. W. Ralston, L. Kilgore, F. B. Wyatt, D. Buchan, J. S. Baker, Weekly training frequency effects on strength gain: a meta-analysis. Sports Medicine-open 4, 1-24 (2018).

3. B. J. Schoenfeld, J. Grgic, J. Krieger, How many times per week should a muscle be trained to maximize muscle hypertrophy? A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining the effects of resistance training frequency. Journal of Sports Sciences 37, 1286-1295 (2019).

4. N. Ratamess et al., Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults [ACSM position stand]. Med Sci Sports Exerc 41, 687-708 (2009).

5. P. Androulakis-Korakakis, J. P. Fisher, J. Steele, The minimum effective training dose required to increase 1RM strength in resistance-trained men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine 50, 751-765 (2020).

6. P. Androulakis-Korakakis et al., The minimum effective training dose required to increase 1RM strength in powerlifters. SportRxiv Preprints (2021).

7. J. W. Krieger, Single vs. multiple sets of resistance exercise for muscle hypertrophy: a meta-analysis. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 24, 1150-1159 (2010).

8. C. E. Garber et al., American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 43, 1334-1359 (2011).

9. A. Paoli, P. Gentil, T. Moro, G. Marcolin, A. Bianco, Resistance training with single vs. multi-joint exercises at equal total load volume: effects on body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness, and muscle strength. Frontiers in Physiology 8, 1105 (2017).

10. R. Carpinelli, A critical analysis of the national strength and conditioning association’s opinion that free weights are superior to machines for increasing muscular strength and power. Medicina Sportiva Practica 18, 21-39 (2017).

11. A. H. Saeterbakken, R. van den Tillaar, M. S. Fimland, A comparison of muscle activity and 1-RM strength of three chest-press exercises with different stability requirements. Journal of Sports Sciences 29, 533-538 (2011).

12. J. Padulo, P. Mignogna, S. Mignardi, F. Tonni, S. D’ottavio, Effect of different pushing speeds on bench press. International Journal of Sports Medicine 33, 376-380 (2012).

13. T. J. Suchomel, S. Nimphius, C. R. Bellon, M. H. Stone, The importance of muscular strength: training considerations. Sports Medicine 48, 765-785 (2018).

Acknowledgements

Images provided by jacoblund and DrMonochrome

Disclaimer

The material displayed on this website is provided without any guarantees, conditions or warranties as to its accuracy.

Information written and expressed on this website is for education purposes and interest only. It is not intended to replace advice from your medical or healthcare professional.

You are encouraged to make your own health care choices based on your own research and in conjunction with your qualified practitioner.

The information provided on this website is not intended to provide a diagnosis, treatment or cure for any diseases. You should seek medical attention before undertaking any diet, exercise, other health program or other procedure described on this website.

To the fullest extent permitted by law we hereby expressly exclude all warranties and other terms which might otherwise be implied by statute, common law or the law of equity and must not be liable for any damages whatsoever, including but without limitation to any direct, indirect, special, consequential, punitive or incidental damages, or damages for loss of use, profits, data or other intangibles, damage to goodwill or reputation, injury or death, or the cost of procurement of substitute goods and services, arising out of or related to the use, inability to use, performance or failures of this website or any linked sites and any materials or information posted on those sites, irrespective of whether such damages were foreseeable or arise in contract, tort, equity, restitution, by statute, at common law or otherwise.

Ten Minutes is All You Need

Research has shown that ten minutes of moderate-to-vigorous exercise performed each day is enough to significantly reduce your risk of early death.

Ten Minutes is All You Need

Research has shown that ten minutes of moderate-to-vigorous exercise performed each day is enough to significantly reduce your risk of early death.