Face the Future

1. Introduction

One of the great advantages of building your personal resilience is being better positioned for what the future holds. This includes being able to adapt and thrive when faced with adversity and rapid change, or making changes to your life that will optimise your healthspan and enable you to participate and contribute more vigorously in the future world.

But being resilient is also about looking to the bigger picture and considering what the future might bring. Although we’ll discuss the importance of ‘future orientation’ when we unpack the Mind domain of everyday resilience, in today’s article we wanted to highlight upcoming revolution in human health and flourishing that we want to be a part of. But this revolution isn’t a given, and we’ll need to be resilient at the individual, community, and societal level to face the inequality and exploitation that may prevent this future from occurring.

2. The future we want to see

We’ve been strongly influenced by the analysis and vision of the RethinkX Group and their assessment of the positive possibilities that will be unlocked by rapid technological change over the next decade. In their forecast, humanity successfully levers emerging technologies to dramatically reduce the cost of essential goods and services. It is estimated that a modern lifestyle, which includes 1,000 miles/month of transport, 2,000 kWh/month of energy, complete nutrition, 100 litres of clean water/day, ongoing and continuing education, 500 sq. ft. of living space and with communications, could cost less than $250/month by 2030 and around $125/month by 2035 (1).

Moreover, production will become increasingly less reliant on the extraction and exploitation model of production that has been the foundation of human economies throughout history. This economic and technological transformation is expected to provide a high standard of living for everyone and dramatically increase human flourishing (1).

We predict that societies geared towards human flourishing will have a scale-free, loosely connected topology, a strong commitment to human rights, and an egalitarian philosophy that encourages diversity. This type of system requires a focus on ideas rather than ideology, is deeply connected to objective reality, and embraces complexity and systems thinking.

This is the type of society that we want our nephews, nieces, children, and grandchildren to grow up in. Therefore, this is the society that we, as a company, are actively working towards.

3. The trends steering us from this future

What’s preventing this future from manifesting tomorrow? It’s not a quick answer. To understand the deep, historical trends that work against a future of human flourishing, we need to step back and take a moment to understand the dominant ‘boom-bust’ cycle that has characterised human history. If we understand this cycle better, we can plan our resilience accordingly and intentionally re-shape these forces towards a future of our choosing.

3.1 The Agricultural Revolution kicks off the boom-bust cycle

Humans existed as foragers and hunter-gatherers for over 2 million years (2). Then around 12,000 years ago, something incredible happened: we discovered agriculture (2). At this point, human population expansion increased roughly five-fold (2), giving rise to a dramatic population increase known as the Neolithic Demographic Transition (NDT).

It’s been previously assumed that the invention of agriculture led to a steady increase in the global human population (2, 3). However, studies have shown that these early farming communities experienced continual cycles of ‘boom’ and ‘bust’ (3). Further, these cycles did not correlate with changing weather patterns, suggesting that agricultural boom-bust cycles were instead driven largely by social factors (4).

3.2 The rise and collapse of civilisation is common throughout our history

Unfortunately, the repeated rise and subsequent collapse of civilisations throughout history confirm that human civilisations are naturally prone to collapse (5).

Mesopotamia offers a great example of this disposition. Often considered the ‘cradle of civilisation’, Mesopotamia has seen the rise and fall of a host of civilisations including the Sumerian, Akkadian, Assyrian, Babylonian, Achaemenid, Seleucid, Parthian, Sassanid, Umayyad, and Abbasid Empires (5, 6). In China, the Zhou, Han, Tang, and Song Empires all rose to power and then collapsed (5, 6). In the Americas, the Maya, Teotihuacan, Cahokia, Pueblo and Hohokam similarly rose and then declined (5, 6). The Mauryan and the Gupta Empires of the Indian sub-continent rose and fell, as did many impressive civilisations across both South East Asia and Africa (5, 6).

One might think that modern, sophisticated societies are immune to the societal collapse that plagued the ancient world. However, the historical record suggests otherwise (5, 6). Advanced, complex, and powerful societies were just as susceptible to collapse as less developed civilisations. The Roman, Assyrian, Han, Mauryan, and Gupta Empires were all culturally and technologically sophisticated societies, yet they all collapsed or irreversibly declined (5, 6).

Thus, the historical record bears testimony that many advanced, powerful civilisations have collapsed during the past five thousand years. In general, civilisation collapse is accompanied by war, famine, and disease, followed by centuries of population loss, cultural decline, and economic regression.

3.3 Why does this keep happening?

Historical analyses and modelling approaches have uncovered conserved mechanisms that are common themes to civilisational collapse (5, 6). The first recipe for a collapse is when a civilisation exceeds the carrying capacity of its ecosystem (6). When a civilisation extracts more from nature than nature can replenish, then collapse is imminent (6). The extent of the civilisational collapse depends on how the level of extraction compares to the carrying capacity of the natural system. If nature can recover, then so too can the civilisation. However, large overshoots of nature’s carrying capacity lead to devastating collapses. If extraction drives the natural system into permanent decline, then the civilisation suffers permanent collapse (6).

Of more relevance to modern society are the negative effects of economic stratification (5, 6). Stratification of society into wealthy ‘Elites’ and ‘Commoners’ began in earnest with the agricultural revolution and has remained a permanent fixture throughout our history. History and mathematical modelling suggest that under conditions of significant economic stratification, societal collapse can be difficult to avoid (5, 6).

The presence of wealthy elites contributes to a societal decline in several ways. First, as the elite’s consumption grows, it leads to famine in the commoners, the loss of workers, excessive resource extraction from the natural system and eventual societal collapse (6). Second, wealth buffers the elites from the early stages of societal decline. Further, a long, apparently stable ‘business as usual’ trajectory often precedes societal collapse. This combines with the buffering effects of wealth to detach the elite’s from reality, and they are caught entirely unawares when society collapses (6). Third, the conflict between competing factions within the ruling elite factions can destabilise society (5). Finally, continual exploitation of commoners by the elites can trigger revolution (5).

3.4 What’s different this time?

Although historical accounts of societal collapse are a compelling cautionary tale, directly extrapolating from historical case studies to the 21st century is not straightforward due to key differences between today’s society and those past civilisations that have undergone collapse. Some of these include:

3.4.1 Reductions in poverty

Throughout much of history, commoners have existed at a subsistence or slightly above subsistence levels of existence (5). Fortunately, this sorry state has steadily improved thanks to improved governance, increasing technology, and more sophisticated economic systems. As of 2019 poverty is at its lowest in recorded history.

Although there remains much work to be done to eradicate poverty, our progress to date represents a tremendous advance on the historical situation (5).

3.4.2 Increases in personal freedom

Historically, personal freedom was a luxury. For example, in Athens, two-thirds of people were enslaved (7). In ancient Rome, one-third of the population was enslaved (7). In fact, it is estimated that up until 1800 as much as three-quarters of the world’s population lived in servitude (7).

Thankfully, the festering sore of slavery and servitude has been globally repudiated. Again, this development represents a tremendous and unprecedented advance over historical societies.

3.4.3 Health, education and technology

Our previous article outlined how modern medicine has significantly increased the health, well-being, and longevity of human populations around the world.

Literacy and education levels are clearly much higher now compared to most of history. Literacy, which was once restricted to less than one per cent of the elite population, is now universal in developed nations and rapidly approaching universality in less developed nations.

The most striking difference between the present and the past is technology and wealth production. Modern manufacturing and supply chains, information technology, big data, machine learning, complexity theory, and biotechnology are technological marvels that were unimagined throughout most of human history. Because of this, the standard of living currently enjoyed in industrialised societies far exceeds anything our ancestors ever experienced.

Furthermore, our economic system has fundamentally changed the nature of our ruling elite. Many (but by no means all) of the new elite have risen to the top through innovation and bringing new solutions and technology to market. This is fundamentally different from the zero-sum game of blatant exploitation typical in ages past (5).

3.4.4 Existential Risk

Existential risk was first defined as ‘an adverse outcome would either annihilate Earth-originating intelligent life or permanently and drastically curtail its potential’ (8). Unfortunately, the probability of humans going extinct has never been higher (9).

The recent increase in existential risk is being driven largely by our increasing technology combined with the ever-increasing interconnectedness of the modern world (8, 9). Some examples of human-made existential risks are nuclear war, pandemics, machine learning, runaway nanotechnology, climate change, and ecosystem collapse (8).

4. Preparing for transition, adversity, and rapid change

Analysts considerably more knowledgeable than ourselves have studied the current situation and concluded that we are currently experiencing a ‘societal phase-transition’ (10). Societal phase transitions during which our current societies are transitioning from our current stable-state to another stable-state (10).

Societal phase-transitions are accompanied by a variety of societal stressors that are symptoms of underlying change. Briefly, our current transition is marked by:

– increasing inequality, with rapidly diverging wealth between the ‘top one per cent’ elites and everyone else

– social unrest, political polarisation, and the rise of political extremism

– the absence of any real solutions proposed within the political discourse

– crony capitalism, government corruption, and the systematic dismantling of established safeguards and checks-and-balances

– subversion of the rule of law

– economic instability, rising unemployment, and the erosion of the middle class

Some underlying drivers include:

– disruption of every economic sector by increasingly rapid technological innovations

– globalisation and automation

– increasing inequality and economic insecurity

– the emergence of competing systems of governance that will likely eclipse the Western democratic system in terms of both economic and technological capabilities

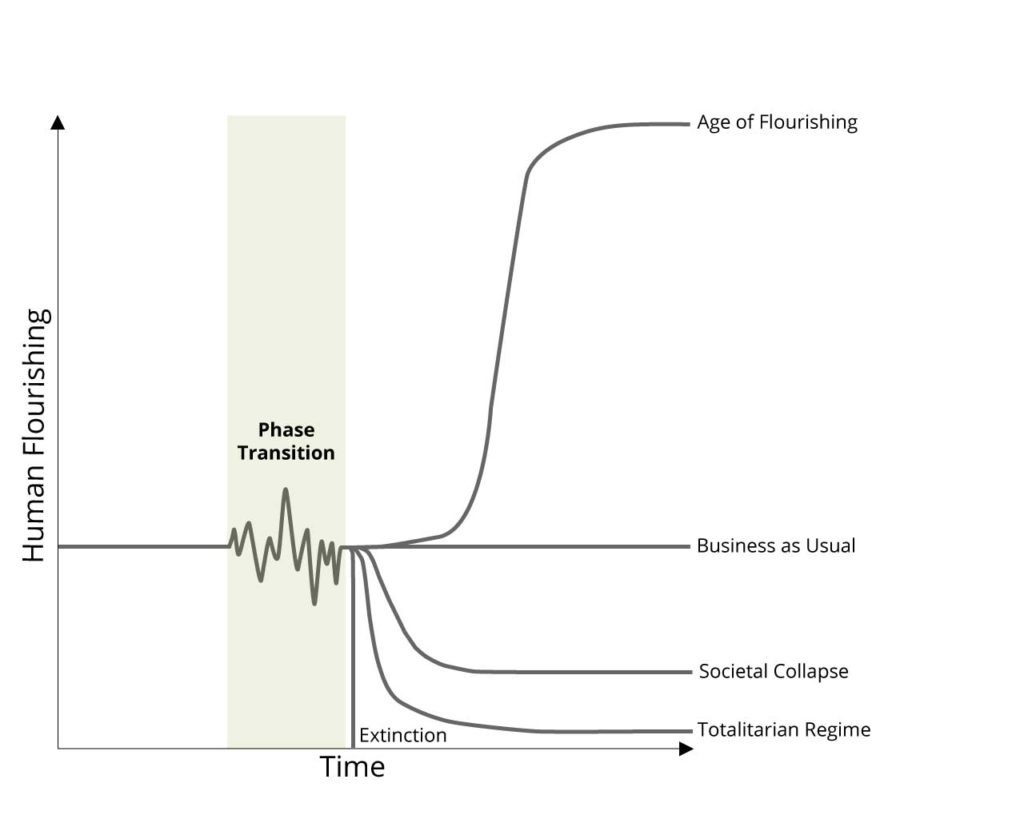

When you consider our current societal stressors, the dominant boom-bust cycle prevalent in human history, and the underlying drivers influencing the present, five potential pathways can be readily identified. These are:

4.1 Business as usual

It could be argued that society will continue along more-or-less the same trajectory, with the current political and economic instabilities representing normal and expected fluctuations. This argument has been considered and dismissed by experts for the following reasons (10):

– every major economic sector is now experiencing tremendous disruption driven by emerging technologies

– the re-emergence of competing, aggressive, and technologically sophisticated state actors are actively applying external pressure on our systems of governance and commerce

– the current Western political and economic institutions have become brittle and unresponsive (10)

4.2 The emergence of totalitarian systems of government

There are many different flavours of totalitarianism. These include fascism, theocracies, monarchies, oligarchies, monopolies, communist and socialist regimes, and military-industrial complexes. The ruling elite within these various regimes can be determined by race, class, family, or political connection. No matter which ideologies are espoused, one can be assured that all forms of totalitarianism are simply a rebranding of the classic elite/commoner societal structure that has been a hallmark of most human civilisations.

The structure of totalitarian regimes is generally top-down, hierarchical, suppresses diversity and personal freedom, favours the ruling class of elites, appeals to simple ideology, and avoids complexity or complex thinking.

For the first time in history, the development of new technologies such as facial recognition, big data analysis, machine learning, and automation has provided totalitarian regimes with the tools that could empower them in perpetuity. This makes the 21st Century a particularly dangerous phase of human history, because if totalitarian regimes become established, we may never see the end of them.

4.3 Societal Collapse

Historically, periods of intense upheaval are often followed by a civilisational collapse that triggers economic ruin or complete annihilation (5). Thus, there is a possibility that the current phase transition could end in the collapse of Western and perhaps global civilisation (1).

Proposed drivers of civilisational collapse include combinations of climate change, famine, social unrest driven by increasing inequality, economic instability and disease (1).

4.4 Extinction

As outlined earlier, our technological leaps have greatly increased the risk of human extinction (9). This probability is likely to increase during times of global distress. The most obvious risk during periods of political and economic instability is a war that escalates into a nuclear exchange between two or more nuclear superpowers (9). However, other plausible scenarios include a global tragedy of the commons with agricultural collapse followed by total ecosystem collapse, or global instabilities fuelling the formation of hi-tech terror groups unleashing engineered bioweapons.

In general, our global connectivity (10) combined with emerging technologies (9) have made our species more vulnerable to anthropomorphic extinction events. At the same time, ongoing political instability and polarisation decrease our ability to mount effective national and global responses to these emerging threats.

4.5 A transition to an age of human flourishing

We summarised this pathway at section two of this article and we consider this pathway the only desirable outcome. To this effect, Wise Seed is currently engaged in a range of initiatives and advocacy orientated towards making this future happen.

5. Conclusion

A study of human history reveals a repeating pattern of elite and commoner societal stratification and continuing cycles of civilisational boom and bust. This pattern is highly conserved. It appears in all periods of history, on all continents, and across all cultures.

Our global civilisation and increased technologies have greatly increased the risk that this cycle of rise and fall entails significant risk, not least of which is the extinction of our species. However, for the first time in history, we now have an opportunity to break from the boom-bust cycle and enter a new phase of human flourishing.

Whether we choose the path to flourishing or continue with the established boom-bust approach is now up to us. Regardless, a focus on building resilience at the individual, community, and society level is a necessary component of orientating to a future characterised by rapid change, adversity, and opportunity.

6. References and Further Reading

1. J. Arbib, Seba, T, Rethinking Humanity: Five Foundational Sector Disruptions, the Lifecycle of Civilizations, and the Coming Age of Freedom. (2020).

2. J.-P. Bocquet-Appel, When the world’s population took off: the springboard of the Neolithic Demographic Transition. Science 333, 560-561 (2011).

3. C. R. Gignoux, B. M. Henn, J. L. Mountain, Rapid, global demographic expansions after the origins of agriculture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 6044-6049 (2011).

4. S. Shennan et al., Regional population collapse followed initial agriculture booms in mid-Holocene Europe. Nature Communications 4, 1-8 (2013).

5. W. Scheidel, The Great Leveller: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century. (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2018).

6. S. Motesharrei, J. Rivas, E. Kalnay, Human and nature dynamics (HANDY): Modelling inequality and use of resources in the collapse or sustainability of societies. Ecological Economics 101, 90-102 (2014).

7. J. C. Scott, Against the grain: a deep history of the earliest states. (Yale University Press, 2017).

8. N. Bostrom, Existential risks: Analyzing human extinction scenarios and related hazards. Journal of Evolution and Technology 9, (2002).

9. T. Ord, The precipice: existential risk and the future of humanity. (Hachette Books, 2020).

N. N. Taleb, The black swan: The impact of the highly improbable. (Random House, 2007), vol. 2.

Ten Minutes is All You Need

Research has shown that ten minutes of moderate-to-vigorous exercise performed each day is enough to significantly reduce your risk of early death.

Ten Minutes is All You Need

Research has shown that ten minutes of moderate-to-vigorous exercise performed each day is enough to significantly reduce your risk of early death.